Carolingian dynasty

The Carolingian dynasty (known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolings, or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family with origins in the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD. The name "Carolingian", Medieval Latin karolingi, an altered form of an unattested Old High German *karling, kerling (meaning "descendant of Charles", cf. MHG kerlinc),[1] derives from the Latinised name of Charles Martel: Carolus.[2] The family consolidated its power in the late 7th century, eventually making the offices of mayor of the palace and dux et princeps Francorum hereditary and becoming the de facto rulers of the Franks as the real powers behind the throne. By 751, the Merovingian dynasty which until then had ruled the Franks by right was deprived of this right with the consent of the Papacy and the aristocracy and a Carolingian, Pepin the Short, was crowned King of the Franks.

History

Traditional historiography has seen the Carolingian assumption of kingship as the product of a long rise to power, punctuated even by a premature attempt to seize the throne through Childebert the Adopted. This picture, however, is not commonly accepted today. Rather, the coronation of 751 is seen typically as a product of the aspirations of one man, Pepin, and of the Church, which was always looking for powerful secular protectors and for the extension of its spiritual and temporal influence.

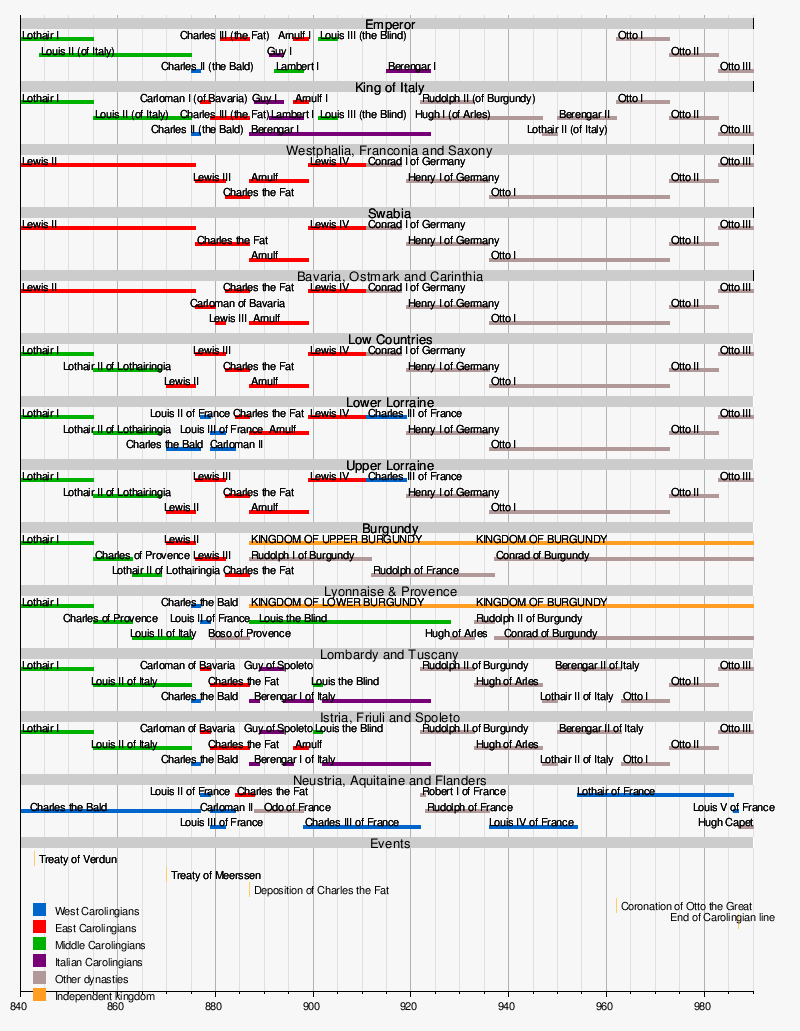

The greatest Carolingian monarch was Charlemagne, who was crowned Emperor by Pope Leo III at Rome in 800. His empire, ostensibly a continuation of the Roman Empire, is referred to historiographically as the Carolingian Empire. The traditional Frankish (and Merovingian) practice of dividing inheritances among heirs was not given up by the Carolingian emperors, though the concept of the indivisibility of the Empire was also accepted. The Carolingians had the practice of making their sons (sub-)kings in the various regions (regna) of the Empire, which they would inherit on the death of their father. Following the death of Louis the Pious, the surviving adult Carolingians fought a three-year civil war ending only in the Treaty of Verdun, which divided the empire into three regna while according imperial status and a nominal lordship to Lothair I. The Carolingians differed markedly from the Merovingians in that they disallowed inheritance to illegitimate offspring, possibly in an effort to prevent infighting among heirs and assure a limit to the division of the realm. In the late ninth century, however, the lack of suitable adults among the Carolingians necessitated the rise of Arnulf of Carinthia, a bastard child of a legitimate Carolingian king.

The Carolingians were displaced in most of the regna of the Empire in 888. They ruled on in East Francia until 911 and they held the throne of West Francia intermittently until 987. Though they asserted their prerogative to rule, their hereditary, God-given right, and their usual alliance with the Church, they were unable to stem the principle of electoral monarchy and their propagandism failed them in the long run. Carolingian cadet branches continued to rule in Vermandois and Lower Lorraine after the last king died in 987, but they never sought thrones of principalities and made peace with the new ruling families. It is with the coronation of Robert II of France as junior co-ruler with his father, Hugh Capet, the first of the Capetian dynasty, that one chronicler of Sens dates the end of Carolingian rule.[3]

The dynasty became extinct in the male line with the death of Odo, Count of Vermandois. His sister Adelaide, the last Carolingian, died in 1122.

List of Carolingians

This is an incomplete listing of those of the male-line descent from Charles Martel:

Charles Martel (676–741) had five sons;

- 1. Carloman, Mayor of the Palace (711–754) had two sons;

- A. Drogo, Mayor of the Palace (b. 735)

- 2. Pepin the Short (714–768) had two sons;

- A. Charlemagne (747–814) had eight sons;

- I. Pepin the Hunchback (769–811) died without issue

- II. Charles the Younger (772–811) died without issue

- III. Pepin of Italy (773–810) had one son (illegitimate);

- a. Bernard of Italy (797–818) had one son;

- i. Pepin, Count of Vermandois (b. 815) had three sons;

- 1. Bernard, Count of Laon (844–893) had one son;

- A. Roger I of Laon (d. 927) had one son;

- I. Roger II of Laon (d. 942) died without male issue

- 2. Pepin, Count of Senlis and Valois (846–893) had one son;

- A. Pepin II, Count of Senlis, (876–922) had one son;

- I. Bernard of Senlis (919–947) had one son;

- a. Robert I of Senlis (d. 1004) had one son;

- i. Robert II of Senlis and Peroone (d. 1028) died without male issue

- 3. Herbert I, Count of Vermandois (848–907) had two sons;

- A. Herbert II, Count of Vermandois (884–943) had five sons;

- I. Odo of Vermandois (910–946) died without issue

- II. Herbert, Count of Meaux and of Troyes (b. 911–993)

- III. Robert of Vermandois (d. 968) had one son;

- a. Herbert III, Count of Meaux (950–995) had one son;

- i. Stephen I, Count of Troyes (d. 1020) died without issue

- IV. Adalbert I, Count of Vermandois (916–988) had four sons;

- a. Herbert III, Count of Vermandois (953–1015) had three sons;

- i. Adalbert II of Vermandois (c.980–1015)

- ii. Landulf, Bishop of Noyon

- iii. Otto, Count of Vermandois (979–1045) had three sons;

- 1. Herbert IV, Count of Vermandois (1028–1080) had one son;

- A. Odo the Insane, Count of Vermandois (d. after 1085)

- B. Adelaide, Countess of Vermandois (d. 1122)

- 2.Eudes I, Count of Ham, (b. 1034)

- 3.Peter, Count of Vermandois

- b. Odo of Vermandois (c. 956-983)

- c. Liudolfe of Noyon (c. 957-986)

- d. Guy of Vermandois, Count of Soissons

- V. Hugh of Vermandois, Archbishop of Rheims (920-962) died without issue

- IV. Louis the Pious (778–840) had 4 sons;

- a. Lothair I (795–855) had 4 sons;

- i. Louis II of Italy (825–875) died without male issue

- ii. Lothair II of Lotharingia (835–869) had 1 son (illegitimate);

- 1. Hugh, Duke of Alsace (855–895) died without issue

- iii. Charles of Provence (845–863) died without issue

- iv. Carloman (b. 853) died in infancy

- b. Pepin I of Aquitaine (797–838) had 2 sons;

- i. Pepin II of Aquitaine (823–864) died without issue

- ii. Charles, Archbishop of Mainz (828–863) died without issue

- c. Louis the German (806–876) had 3 sons;

- i. Carloman of Bavaria (830–880) had 1 son (illegitimate);

- 1. Arnulf of Carinthia (850–899) had 3 sons;

- A. Louis the Child (893–911) died without issue

- B. Zwentibold (870–900) died without issue

- C. Ratold of Italy (889–929) died without issue

- ii. Louis the Younger (835–882) had 1 son;

- 1. Louis (877 - 879) died in infancy

- iii. Charles the Fat (839–888) had 1 son (illegitimate);

- 1. Bernard (son of Charles the Fat) (d. 892 young)

- d. Charles the Bald (823–877) had 4 sons;

- i. Louis the Stammerer (846–879) had 3 sons;

- 1. Louis III of France (863–882) died without issue

- 2. Carloman II of France (866–884) died without issue

- 3. Charles the Simple (879–929) had one son;

- A. Louis IV of France (920–954) had five sons;

- I. Lothair of France (941–986) had two sons;

- a. Louis V of France (967–987) died without issue

- b. Arnulf, Archbishop of Reims (d. 1021) died without issue

- II. Carloman (b. 945) died in infancy

- III. Louis (b. 948) died in infancy

- IV. Charles, Duke of Lower Lorraine (953–993) had 3 sons;

- a. Otto, Duke of Lower Lorraine (970–1012) died without issue

- b. Louis of Lower Lorraine (980–1015) died without issue, the last legitimate Carolingian

- c. Charles (b. 989) died young

- V. Henry (b. 953) died in infancy

- ii. Charles the Child (847–866) died without issue

- iii. Lothar (848–865) died without issue

- iv. Carloman, son of Charles the Bald (849–874) died without issue

- V. Lothair (778–780) died in infancy

- VI. Drogo of Metz (801–855) died without issue

- VII. Hugh, son of Charlemagne (802–844) died without male issue

- VIII. Dietrich (Theodricum) (807-818) died without male issue

- B. Carloman I (751–771) died without issue

- 3. Grifo (726–753) died without issue

- 4. Bernard, son of Charles Martel (730–787) had two sons;

- A. Adalard of Corbie (751–827) died without issue

- B. Wala of Corbie (755–836) died without issue

- 5. Remigius of Rouen (d. 771) died without issue

See also

Sources

- Hollister, Clive, and Bennett, Judith. Medieval Europe: A Short History.

- Reuter, Timothy. Germany in the Early Middle Ages 800–1056. New York: Longman, 1991.

- MacLean, Simon. Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the end of the Carolingian Empire. Cambridge University Press: 2003.

- Lewis, Andrew W. (1981). Royal Succession in Capetian France: Studies on Familial Order and the State. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-77985-1.

- Leyser, Karl. Communications and Power in Medieval Europe: The Carolingian and Ottonian Centuries. London: 1994.

- Oman, Charles. The Dark Ages, 476-918. 6th ed. London: Rivingtons, 1914.

- Painter, Sidney. A History of the Middle Ages, 284-1500. New York: Knopf, 1953.

- "Astronomus", Vita Hludovici imperatoris, ed. G. Pertz, ch. 2, in Mon. Gen. Hist. Scriptores, II, 608.

- Reuter, Timothy (trans.) The Annals of Fulda. (Manchester Medieval series, Ninth-Century Histories, Volume II.) Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992.

- Einhard. Vita Karoli Magni. Translated by Samuel Epes Turner. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1880.

Notes

- ^ Babcock, Philip (ed). Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, Inc., 1993: 341.

- ^ Hollister and Bennett, 97.

- ^ Lewis, 17.